Financial Portfolios and Risks

In this chapter, you will:

- Understand difference between diversifiable and non-diversifiable risk

- Understand the degree of correlation between portfolios and risk

- Understand what are market risk factors

- Understand what are specific risk factors

- Understand the measurement of beta and the assumptions of CAPM

- Understand the concept of SML (Security Market Line)

What is a portfolio? An investment portfolio refers to the group of assets that is owned by an investor. It is possible to construct a portfolio in such a way that the total risk of the portfolio is less than the sum of the risk of the individual assets taken together. Generally, investing in a single security is riskier than investing in a portfolio, because the returns to the investor are based on the future of a single asset. Hence, in order to reduce risk, investors hold a diversified portfolio which might contain equity capital, bonds, real estate, savings accounts, bullion, collectibles and various other assets. In other words, the investor does not put all his eggs into one basket.

Diversifiable and Non-diversifiable Risk

The fact that returns on stocks do not move in perfect tandem means that risk can be reduced by diversification. But the fact that there is some positive correlation means that in practice risk can never be reduced to zero. So, there is a limit on the amount of risk that can be reduced through diversification. This can be traced to two major reasons.

Degree of Correlation

As we have been saying, the amount of risk reduction depends on the degree of positive correlation between stocks. The lower the degree of positive correlation, the greater is the amount of risk reduction that is possible.

The Number of Stocks in the Portfolio

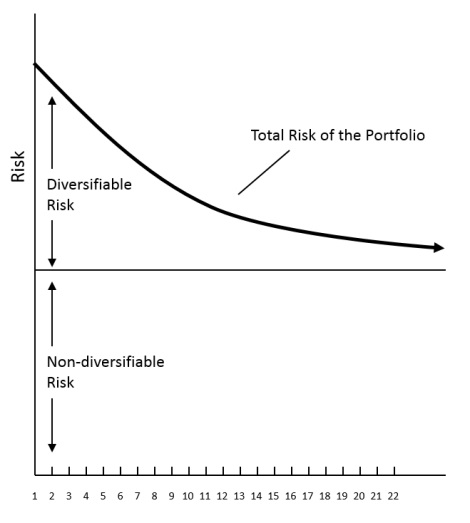

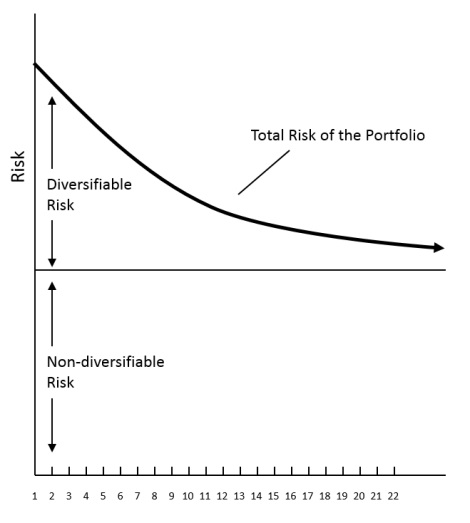

The amount of risk reduction achieved by diversification also depends on the number of stocks in the portfolio. As the number of stocks increases, the diversifying effect of each additional stock diminishes as shown in the figure below:

Risk Reduction through Diversification

As the figure indicates, the major benefits of diversification are obtained with the first 10 to 12 stocks, provided they are drawn from industries that are not closely related. Additions to the portfolio beyond this point continue to reduce total risk but the benefits are diminishing.

From the figure it is also apparent that it is the diversifiable risk that is being reduced unlike the non-diversifiable risk which remains constant whatever your portfolio is. What are diversifiable and non-diversifiable risks? The risk of any individual stock can be separated into two components: non-diversifiable and diversifiable risk.

Non-diversifiable risk is that part of total risk (from various sources like interest rate risk, inflation risk, financial risk, etc.) that is related to the general economy or the stock market as a whole and hence cannot be eliminated by diversification. Non-diversifiable risk is also referred to as market risk or systematic risk.

Diversifiable risk on the other hand, is that part of total risk that is specific to the company or industry and hence can be eliminated by diversification. Diversifiable risk is also called unsystematic risk or specific risk.

Let us take a look at some of the factors that give rise to diversifiable and non-diversifiable risk.

Non-diversifiable or Market Risk Factors

- Major changes in tax rates

- War & other calamities

- An increase or decrease in inflation rates

- A change in economic policy

- Industrial recession

- An increase in international oil prices, etc.

Diversifiable or Specific Risk Factors

- Company strike

- Bankruptcy of a major supplier

- Death of a key company officer

- Unexpected entry of new competitor into the market etc.

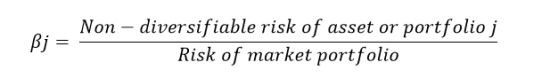

Risk of Stocks in a Portfolio

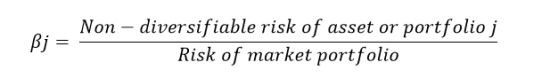

How do you measure the risk of stocks in a portfolio? You can think of a portfolio‘s standard deviation as a good indicator of its risk to the extent that if addition of a stock to the portfolio increases the portfolio’s standard deviation, the stock adds risk to the portfolio. But the risk that a stock adds to a portfolio will depend not only on the stock’s total risk, its standard deviation, but on how that risk breaks down into diversifiable and non-diversifiable risk. If an investor holds only one stock, there is no question of diversification, and his risk is therefore, the standard deviation of the stock. For a diversified investor, the risk of a stock is only that portion of the total risk that cannot be diversified away or its non-diversifiable risk. How do you measure non-diversifiable or market risk? It is generally measured by Beta (β) coefficient. Beta measures the relative risk associated with any individual portfolio as measured in relation to the risk of the market portfolio. The market portfolio represents the most diversified portfolio of risky assets an investor could buy since it includes all risky assets. This relative risk can be expressed as:

Formula of Relative Risk

Thus, the beta coefficient is a measure of the non-diversifiable or systematic risk of an asset relative to that of the market portfolio. A beta of 1.0 indicates an asset of average risk. A beta coefficient greater than 1.0 indicates above-average risk — stocks whose returns tend to be more risky than the market. Stocks with beta coefficients less than 1.0 are of below average risk i.e., less riskier than the market portfolio. An important point to note here is that in the case of the market portfolio, all the possible diversification has been done — thus the risk of the market portfolio is non-diversifiable which an investor cannot avoid. Similarly, as long as the asset’s returns are not perfectly positively correlated with returns from other assets, there will be some way to diversify away its unsystematic risk. As a result beta depends only on non-diversifiable risks.

The beta of a portfolio is nothing but the weighted average of the betas of the securities that constitute the portfolio, the weights being the proportions of investments in the respective securities. For example, if the beta of a security A is 1.5 and that of security B is 0.9 and 60% and 40% of our portfolio is invested in the 2 securities respectively, the beta of our portfolio will be 1.26 (1.5 x 0.6 + 0.9 x 0.4).

Measurement of Beta

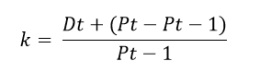

The systematic relationship between the return on the security or a portfolio and the return on the market can be described using a simple linear regression, identifying the return on a security or portfolio as the dependent variable kj and the return on market portfolio as the independent variable km, in the single-index model or market model developed by William Sharpe. This can be expressed as:

kj = αj + βjkm + ej

The beta parameter βj in the model represents the slope of the above regression relationship and as explained earlier, measures the responsiveness of the security or portfolio to the general market and indicates how extensively the return of the portfolio or security will vary with changes in the market return. The beta coefficient of a security is defined as the ratio of the security’s covariance of return with the market to the variance of the market.

The Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM)

The CAPM developed by William F Sharpe, John Lintner and Jan Mossin is one of the major developments in financial theory. The CAPM establishes a linear relationship between the required rate of return of a security and its systematic or undiversifiable risk or beta.

The CAPM is represented mathematically by

kj = Rf + Bj (km - Rf)

where,

kj = expected or required rate of return on security j

Rf = risk-free rate of return

Bj = beta coefficient of security j

km = return on market portfolio.

Assumptions:

- Investors are risk-averse and use the expected rate of return and standard deviation of return as appropriate measures of risk and return for their portfolio. In other words, the greater the perceived risk of a portfolio, the higher return a risk-averse investor expects to compensate the risk.

- Investors make their investment decisions based on a single-period horizon i.e., the next immediate time period.

- Transaction costs in financial markets are low enough to ignore and assets can be bought and sold in any unit desired. The investor is limited only by his wealth and the price of the asset.

- Taxes do not affect the choice of buying assets.

- All individuals assume that they can buy assets at the going market price and they all agree on the nature of the return and risk associated with each investment.

The assumptions listed above are somewhat limiting but the CAPM enables us to be much more precise about how trade-offs between risk and return are determined in financial markets.

In the CAPM, the expected rate of return can also be thought of as a required rate of return because the market is assumed to be in equilibrium. The expected return is the return from an asset that investors anticipate or expect to earn over some future period. The required rate of return for a security is defined as the minimum expected rate of return needed to induce an investor to purchase it.

What do investors require (expect) when they invest? First of all, investors can earn a riskless rate of return by investing in riskless assets like treasury bills. This risk-free rate of return is designated Rf and the minimum return expected by the investors. In addition to this, because investors are risk-averse, they will expect a risk premium to compensate them for the additional risk assumed in investing in a risky asset.

Required Rate of Return = Risk-free rate + Risk premium.

The CAPM provides an explicit measure of the risk premium. It is the product of the Beta for a particular security j and the market risk premium km - Rf

Risk premium = βj (km - Rf)

This beta coefficient ‘βj’ is the non-diversifiable risk of the asset relative to the risk of the market. If the risk of the asset is greater than the market risk. i.e. β exceeds 1.0, the investor assigns a higher risk premium to asset than to the market.

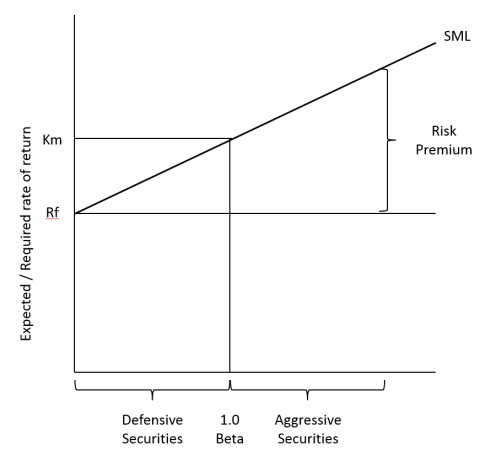

The Security Market Line (SML)

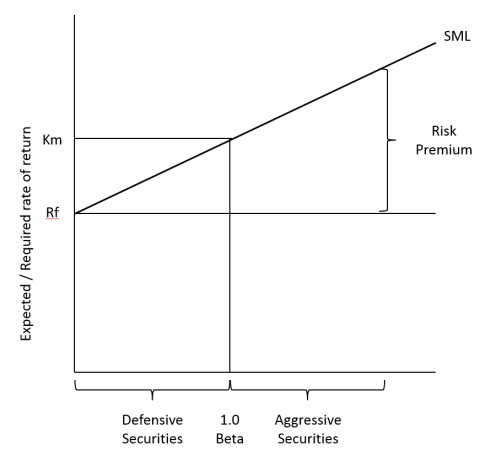

You can plot the relationship between the required rate of return (kj) and non-diversifiable risk (beta) as expressed in CAPM to produce a graph of the SML as shown below:

Risk and Return

As per the CAPM assumptions, any individual security’s expected return and beta statistics should lie on the SML. The SML intersects the vertical axis at the risk-free rate of return Rf and km - Rf is the slope of the SML.

Since all securities are expected to plot along the SML, the line provides a direct and convenient way of determining the expected/required return of a security if you know the beta of the security. The SML can also be used to classify securities. Those with betas greater than 1.00 and plotting on the upper part of the SML are classified as aggressive securities while those with betas less than 1.00 and plotting on the lower part of the SML can be classified as defensive securities which earn below-average returns.

One of the major assumptions of the CAPM is that the market is in equilibrium and that the expected rate of return is equal to the required rate of return for a given level of market risk or beta. In other words, the SML provides a framework for evaluating whether high-risk stocks are offering returns more or less in proportion to their risk and vice-versa. Let us see how we can appraise the value securities using CAPM, and the SML.

Summary:

- An investment portfolio refers to the group of assets that is owned by an investor.

- Returns on stocks do not move in perfect tandem means that risk can be reduced by diversification.

- The amount of risk reduction depends on the degree of positive correlation between stocks.

- As the number of stocks increases, the diversifying effect of each additional stock diminishes.

- The portfolio‘s standard deviation as a good indicator of its risk.

- Beta measures the relative risk associated with any individual portfolio as measured in relation to the risk of the market portfolio.

- The Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) establishes a linear relationship between the required rate of return of a security and its systematic or undiversifiable risk or beta.

MBA INSTITUTE™

MBA INSTITUTE™